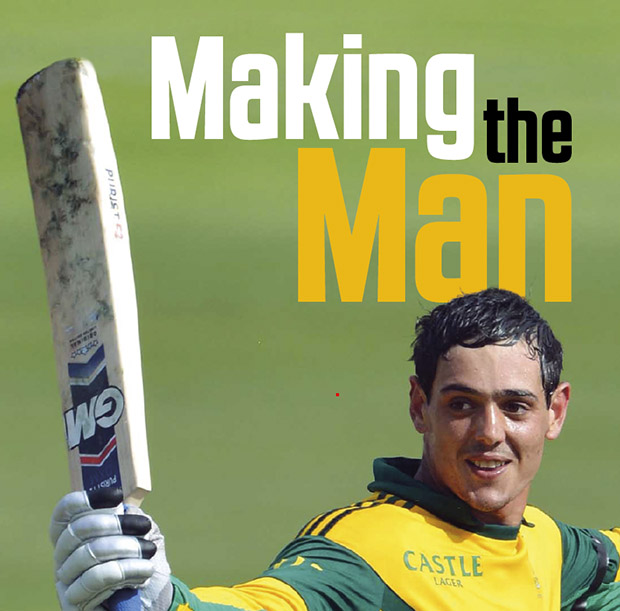

Quinton de Kock has shown his aptitude for international cricket. Now we have to give him the support he needs to build a long and run-laden career for the Proteas.

Let’s take a minute to remind ourselves just how completely insane Quinton de Kock’s world is. Three years ago he was in high school. Now the only maths he requires is to tally up his ever-growing ODI run count (and to count his IPL millions), the only poetry he encounters is the poetry in motion of his batting, and the only physics equation he needs is bat speed x ball speed = force at point of impact.

Not so long ago the players he now calls teammates – the ones he goes on tours with, takes advice from and who have recently stood up to applaud three consecutive ODI hundreds and congratulate him on his Test debut – were his idols. Perhaps their aura is yet to fade for him.

Just how unnatural a situation that is for a 20-year-old (which he was at the time of his debut in international cricket) should never be lost on us. Just because he is a prodigy shouldn’t discount the fact he is, in many senses, still a kid. It should also be put in perspective just how special a player De Kock is. And boy, is he special.

De Kock’s aggressive and imposing approach has elicited comparisons with Herschelle Gibbs, whose career path – schoolboy superstar and domestic destroyer to international powerhouse – resembles his own at this stage. Indeed, Gibbs sees elements of himself in the pup. ‘I like that he’s fearless and doesn’t seem to give a sh*t about his stats,’ Gibbs offers. ‘He is purely instinctive, he keeps it simple and I hope he continues to play that way. He has all the shots. All of them.

‘Later in my career when I started to struggle I thought about technical things I hadn’t before. There’s a place for that, but if I had to do it all over I would have continued to back my instinct more throughout my career. I hope he does.’

Yet talent often has a way of protecting the talented from the desire to improve. Gibbs is arguably the country’s best example of this. The vast majority agreed that he was by some distance the most naturally gifted South African batsman in decades. He was incredible to watch when his talent soared. Having little appreciation for the science of the game, a great Gibbs innings was in every way art, his bat the brush that executed impossibly brilliant strokes and culminated in a masterpiece.

Yet too rarely did that talent consistently translate to performance. He ended his career with averages that betrayed his talent. Memorable he certainly is. But he could have been monumental.

There are lessons for De Kock in Gibbs’ career. It would be remiss not to note that many of those have been heeded and implemented by the Proteas leadership since Gibbs faded from the national frame. De Kock certainly shares a similar philosophy of how the game should be played. But so does AB de Villiers, the telling difference being he has come to have a great appreciation for adapting to match circumstances and grown in his awareness of how important his wicket is to the team’s cause. This amplifies his value and De Kock would do well to position himself in De Villiers’ shadow.

Indeed, beyond De Villiers there are resources to aid De Kock’s rise. A mentorship with former Proteas coach Gary Kirsten would be an excellent start. Kirsten was an accomplished international opening batsman and, more pertinently, has shown to be a master manager of men. The pair worked together at the Dehli Daredevils in the IPL, with De Kock speaking highly of Kirsten’s technical and mental contributions. If not Kirsten, perhaps the retired Graeme Smith. Smith, a pup when he took the Proteas’ reins, has a wealth of knowledge to invest and in De Kock lies the potential for a massive return on such an investment.

This is the most urgent requirement when it comes to the making of De Kock. Preparing him to negotiate the assault on his self-belief that is to come is a far more pressing issue than the debate about his introduction into Test cricket and whether he should keep there.

De Kock won’t continue to carve a swathe through the world’s best attacks at the rate he has started. Failure lurks and will strike. It is no respecter of talent. Whether he will come through that and proceed to build a career akin to the last Proteas wunderkind, De Villiers, or fire then fade like Gibbs, remains to be seen. Nobody can make such a prediction with any certainty, at least not until we have greater insight into his mental constitution.

It hasn’t been tested in a meaningful way just yet. Apart from a brief period in Sri Lanka in 2013, De Kock has yet to taste failure in cricket, certainly not extended periods of strife, the kind that forces self-examination and demands immense resolve. He dominated schoolboy cricket, was the man in the junior international set-up, stood a class apart at domestic level and has taken to international competition with consummate ease. De Kock only knows success. Red-hot rookies, having never been required to deal with the consequences of failure, have often crumbled at the first sight of it. De Kock must be equipped with the required mental arsenal for this battle.

I would suggest the Proteas need De Kock to fail sooner rather than later because it is in his response to that failure that the measure of the player will be revealed.

When this dark time comes De Kock will be able to lean on a number of his teammates – including the majestic De Villiers – as pillars of support. De Villiers sprung out of the Test gates like a greyhound on speed, but then went 16 ODI innings without getting to 50. He had credit in the bank with the selectors given his Test form, and they accepted his struggles were in keeping with those of an immensely gifted rookie, not a terminally flawed one. Hashim Amla showed similar resolve, recovering from being dropped to become one of the game’s pre-eminent Test and ODI batsmen.

History will show that the very highest calibre of players recover from setbacks and thrive thereafter. Former South Africa U19 coach Ray Jennings worked closely with De Kock before his international breakthrough and believes he is made of the right stuff.

‘He stands out as one of the best I’ve coached,’ Jennings says. ‘Technically he isn’t textbook, but if you look at the most successful international players at present, very few of them are. He showed his class against India, who at the time were the No 1 ODI side in the game. Regarding his ability to deal with setbacks, the best players have more than pure talent. They have a mental strength that sets them apart. I’ve seen glimpses of that in Quinton. He’ll be tested in the near future and I believe he’ll come through if he is given the support of the selectors, media and public.’

De Kock’s future is unknown. He’ll write his own story and dictate the length of it. It’s a position many international cricketers would covet. Yet to get caught up in the future would be to miss the most pressing present needs for De Kock. There’ll be more prodigies to come and indeed there already is one of immense promise in the form of SA U19 opener and captain Aiden Markram. But we have to move past the next-big-thing fascination we have as the South African sporting fraternity. Clearly De Kock has a responsibility to not betray his gift. And those entrusted with nurturing him have to spend themselves in an effort to get the very best out of him.

I would suggest they surround him with those capable of building the best man they can. The by-product of that will be a sensational cricketer for South Africa.

Photo: Anne Laing/HSM Images

This feature article was first published in issue 125 of SA Cricket magazine