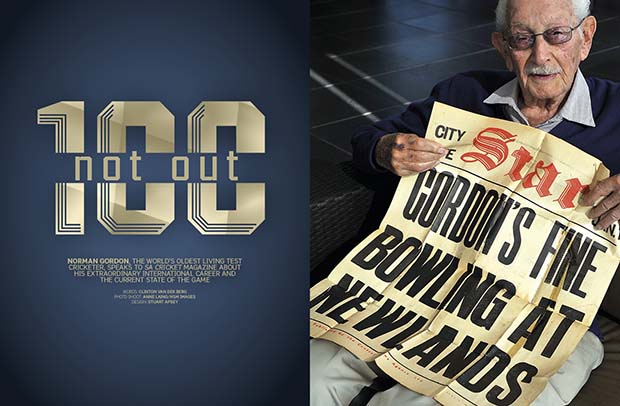

Norman Gordon, the world’s first Test cricketer to reach the age of 100, passed away peacefully on 2 September at 103. SA Cricket magazine spoke to him on the occasion of his 100th birthday three years ago, about his extraordinary international career and the current state of the game. By Clinton van der Berg.

You can easily imagine the 1930s being a gentler age; a time of lazy afternoons, common courtesies and homespun values. A time of smart sensibilities, good graces and elegance.

You can also imagine Norman Gordon being part of this genteel old world. Even now, 70-odd years later, he remains dapper and refined, his slicked-back hair a throwback to his distant, mellifluous past.

Gordon is the world’s oldest living Test cricketer, a centurion who straddles vastly different eras and can offer a rare peak into the world that once was.

Sitting in the soft light of the Houghton Golf Club with his son Brian, a youngster by comparison – he is 67 – Gordon is in excellent spirits when he speaks to SA Cricket magazine just weeks after turning 100, on 6 August 2011.

Hours before being interviewed, Cricket South Africa had been in touch, telling him that he could attend any match he liked at the Wanderers, where they would look after his every need. As is indeed the case at the golf club where he has been a member for 58 years. He and Brian were recently given the freedom of the clubhouse – all meals and drinks are now on the house.

When they are in Johannesburg, father and son visit the golf club nearly every day, looking out over the lush Jack Nicklaus course, although the most extravagant drink for Norman is an iced tea.

The offer of free golf remains, but after failing eyesight he had to give up the game at 96. Aged 87, he scored a hole-in-one. The story goes that when Gary Player was once sitting on the club’s terrace, he noticed Gordon amble up.

‘How did it go?’ asked Player.

‘Broke 70,’ said Gordon.

‘In that case, why do you look so dejected? I’d like to break 70 shots myself.’

‘Who’s talking about shots? I’m talking about clubs,’ quipped Gordon.

Sitting in his favourite corner, people wander up and friends come and say hello to the man they nicknamed Mobil on account of him slicking back his hair with gobfuls of Vaseline. He is, by all measures, a very special member of the club.

‘I have wonderful friends and I can’t credit them enough for everything they’ve done,’ he says.

While Norman lives in a flat in Hillbrow, with its attendant harshness and bright lights, his many friendships mean that he is seldom home. He has just been to the Kruger Park thanks to the generosity of a close friend (although his 30-35% vision hindered his appreciation of the animals), while he is anticipating a two-month holiday at a club member’s home in Plettenberg Bay, free of charge. And then in December, another friend will be hosting the pair in Yzerfontein on the West Coast.

‘It’s better than sitting in Hillbrow watching TV,’ he says wryly, the sepia-stained news clippings edging out from a photo album he had brought along.

Brian lets it be known that these gestures aren’t handouts to a former sportsman hard on his luck; a point he is keen to emphasise after CNN claimed his father was penniless during a recent tribute. ‘That’s nonsense.’

Long-standing friend Ali Bacher recently arranged his 100th birthday celebration at the Wanderers. It says something of Norman’s stature that every cricketer who was invited to attend did so without hesitation. The fast bowlers’ club was there en masse: Neil Adcock, Shaun Pollock, Peter Pollock, Fanie de Villiers, Mike Procter, Makhaya Ntini and Steven Jack. So too Graeme Pollock.

Gordon is still in remarkably good shape. Trim, energetic and engaging, he credits a life of few vices. ‘I never smoked and I might have had a beer only on a very hot day. I could bowl all day without getting tired … remember, we had eight-ball overs then.’

Ironically, he suffered from rheumatism early in life and was warned that he would be unable to run. So much for that.

Gordon played just five Tests, but his international career was extraordinary for three reasons: he played in the 10-day Timeless Test of 1939 and bowled a world record 92.2 eight-ball overs. He also ended up with more wickets (20) than any other bowler in a five-match series against England at a time when the wickets favoured batsmen.

Sir Leonard Hutton reckoned Gordon was the best South African bowler he faced, while the incomparable England captain Wally Hammond compared him to Maurice Tate at his best. High praise indeed.

Gordon recalls the Timeless Test with great clarity. ‘After we batted, the opposition had to make more than 600 [696]. I thought we would win easily, but in the end the wicket was crumbling and I thought we would have got beaten had it gone on [the Test had to be called off because England’s ship was leaving the next day].

‘They would have got the runs [England were on 654-5]. The crowds were huge. The wickets weren’t covered either, so if there was overnight rain or early-morning dew it was like bowling on glass.’

In the event he took one wicket for 256 runs and was happy to bowl 10 to 15 overs at a stretch. He was no fan of the Timeless Test then – ‘it was a mistake 70 years ago’ – and he poo-poohs talk of a return to such now.

Born in Boksburg on the East Rand, he attended Jeppe Boys’ High. He was a fine cricketer, but his contemporaries reckoned he was an even better footballer. ‘I lived in Orwell Street in Kensington and there was a vacant stand next door,’ he recalls.

‘I would be out there every day, come rain or shine, summer or winter. My Latin master, Mr Childe, encouraged me. “Just bowl a good length. You don’t have to clean bowl.” And how it worked.’

So obsessed was Gordon with the sport that he purposefully flunked matric so that he could play another year of senior schools cricket.

Four years after making his Transvaal debut, Gordon took the most wickets in a Currie Cup season (39). A year later he made his debut for South Africa.

He says his action and pace was reminiscent of Shaun Pollock’s. ‘I was exactly the same,’ says Gordon. ‘Pollock also kept a wonderful length.’

His first Test victim was Hammond, who remains the best he ever bowled to. ‘There wasn’t a better offside-playing batsman than him, not ever. I asked him why he never hooked the short ball and he said that’s the easiest way to get out.’

Gordon played in all five Tests in the series and took 20 wickets with figures of 7-162 in his first Test.

His aforementioned Latin master once made a speech at one of Gordon’s birthday parties. ‘In 1066 the Normans conquered the English,’ he told the audience. ‘In 1938-39 another Norman conquered the English …’

Gordon could have reasonably expected to be selected again, but South Africa’s 1940 tour to England was cancelled due to the war. Seven years later, he was overlooked despite having taken the best figures of either side during the 1938-39 series.

The air was thick with talk of anti-Semitism, although SA captain Alan Melville flatly refused to be quoted on the subject. Gordon himself makes light of it. During his Test debut, a heckler shouted out, ‘Here comes the rabbi’.

‘He became very quiet after I had taken five wickets in the first innings,’ says South Africa’s first openly Jewish Test cricketer. (Manfred Susskind toured England in 1924, but he pointedly never admitted to his faith).

Gordon later went on to run a sports shop. Among his regular customers were Bacher, and his mom, who bought the future SA captain’s first bat there. ‘I’ve known him since the 1950s,’ says Bacher. ‘He’s the nicest, most modest man and I have huge respect for him.’

More latterly, Gordon practised as an accountant until just six years ago. Frailer than he once was, Gordon admits to having had quite a liking for the ladies in his youth. ‘I got a few phone calls and I couldn’t let them down,’ he says impishly.

He still loves the old game, but his poor sight means he now listens more than he watches. He doesn’t like what he hears. ‘Frankly, I’m not happy with the way the game has gone in administration, what with all the quarrelling and nonsense over missing money. As for Twenty20, it’s not cricket. I don’t know what it is, but it isn’t cricket.’

He never dreamed of the day when blacks would both play and enjoy watching cricket. ‘It’s amazing how many of them do. They come up to me in the building where I live and tell me how they like the game.’

The money that swirls around also troubles the centurion. ‘I would have loved to have earned the money – I received £3 per day for expenses – but I don’t think all the money has done the game any good. There’s so much back-stabbing. Money plays too great a part. Cricketers now earn a fortune for playing the game they love. Fancy being paid to play cricket …

‘As far as sledging goes … Shane Warne was great but he was a nasty bit of work out in the field. The truth is I never heard a dirty word uttered in my entire career. There wasn’t a single argument. We used to go out dancing and eating with the opposition. There were never harsh words, but we were highly competitive.’

It’s a different world, to be sure. Things we take for granted, like cellphones, amaze him. He has never surfed the internet, although recently someone hooked him up on Skype for a call to the UK.

‘I can’t understand how you can do that without wires between South Africa and England,’ he marvels.

He had a nasty scare in April when he broke his arm and typically for a man his age, it took an age to mend.

Hammond apart, Gordon rates Sir Gary Sobers, Brian Lara, Warne, Glenn McGrath and Dennis Lillee as the greatest he has witnessed. Last year, Lara came down to the golf club to meet him.

Lara put out his hand. ‘Do you know who I am, Mister Gordon?’ ‘Of course,’ came the reply.

The West Indian sent a note on the occasion of Gordon’s 100th, remarking that it was wonderful to meet ‘the great master’. Even at 100, there’s no slowing him. He and his son Brian – ‘my best friend without whom I’d be lost’ – drive everywhere they go.

‘We don’t do much talking,’ says Brian, who has cared for his father ever since Mercy, his wife of 63 years, died in 2001. ‘I could do with another set of hands.’

Gordon, the most special of cricketers, admits to having no more ambitions. ‘Cricket has given me everything. It has been a wonderful life.’ A golden age indeed.

This classic feature was first published in issue 113 of SA Cricket magazine.

Photo: Anne Laing/HSM Images